All together now: modelling claims using federated learning

Originally published by The Actuary, September 2021. © The Institute and Faculty of Actuaries.

Click here to read the original article.

Małgorzata Śmietanka, Dylan Liew and Claudio Giorgio Giancaterino demonstrate how to model claims anonymously using federated learning.

As machine learning techniques become more common in the insurance world, it is important to understand that the benefits of artificial intelligence (AI) can only be harnessed through access to very large amounts of data. When the amount of data is limited, simpler traditional techniques such as generalised linear models (GLMs) outperform complicated methods.

However, harvesting more data is easier said than done, even in the era of big data. Data protection requirements are getting increasingly stringent as the world becomes more aware of data privacy and rights.

This article demonstrates how to fit a claims frequency model when the underlying experience data is private, using federated learning to solve the problem of insufficient training data for claims modelling.

The sample data

We used the ‘freMTPL2freq’ French third-party motor claims available on OpenML. This dataset contains the number of claims made on 678,013 car insurance policies, along with various features that are commonly used in underwriting, such as vehicle age, driver age and region. We considered a typical actuarial problem: predicting the number of claims.

Typically, a single insurer will not have access to all datapoints if these represent the entire industry. We therefore assumed that there were 10 insurers in the market and split the data equally among them. The question was how to build an accurate model for the entire dataset with access to only 10% of the population.

Start with a simple model

We built a neural network in PyTorch, but only training on 10% of the data. In practice, insurers might first try a GLM before going into neural networks, but it can be shown that GLMs are special cases of neural networks, and PyTorch could also be used to build a ‘traditional’ Poisson GLM.

While this model’s input data was small, we robustly trained it to make the scenario realistic:

- Data was split into training and validation sets, in order to avoid overfitting and reduce bias

- Performance was evaluated only against the unseen validation data

- Hyperparameters (number of layers in a network, number of nodes, learning rate, structure of the network) were tuned using a Bayesian search algorithm

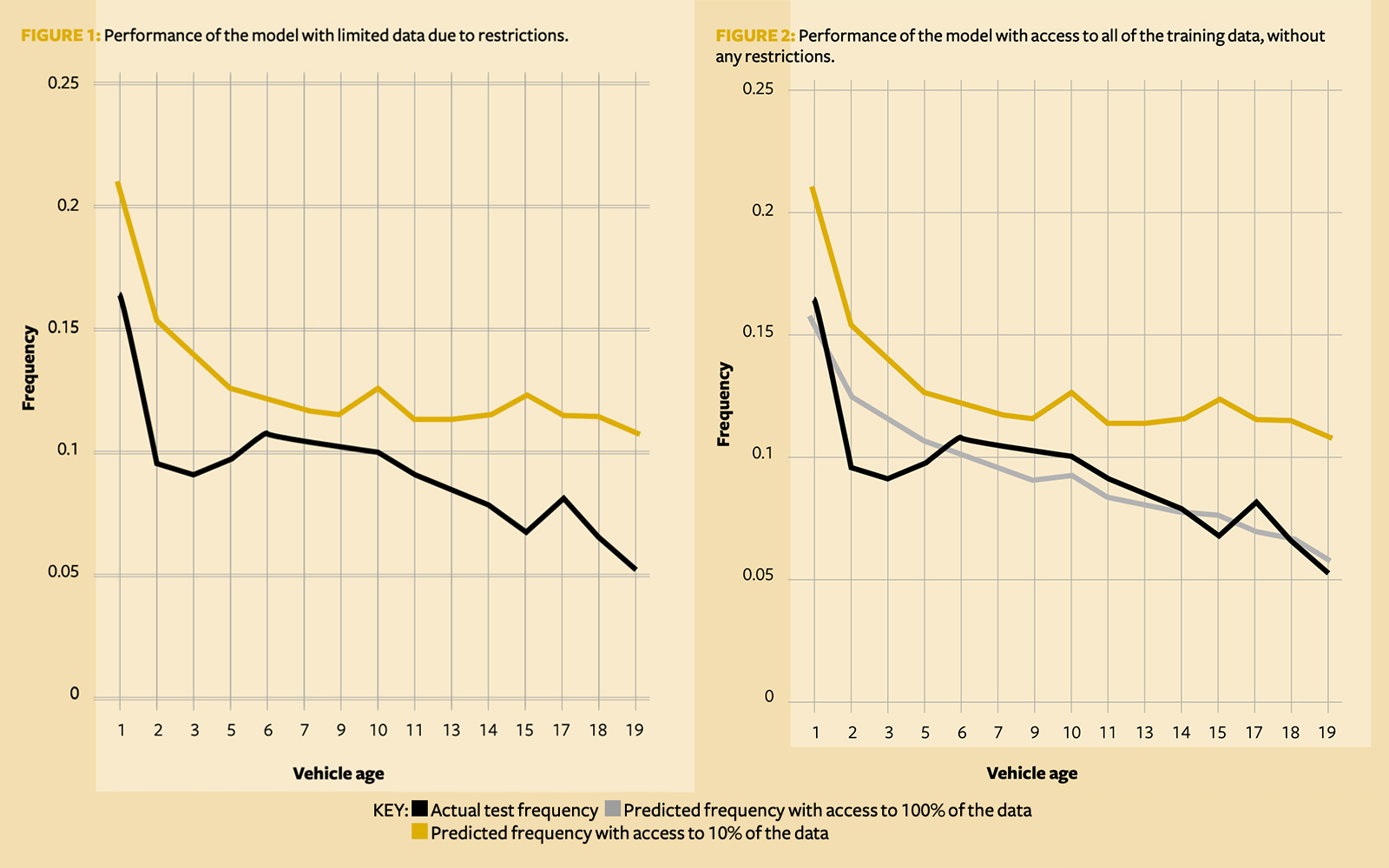

This is a rigorous model pipeline, akin to what a data scientist might do in practice. Unsurprisingly, this partially trained model’s performance is still poor when compared to the global dataset. For example, its predictions compared to the actual claims frequency are poor when looking at the prediction of claims frequency by vehicle age (Figure 1).

In comparison, if we have all of the data and not just 10%, this model yields predictions that are significantly closer to the actual test frequency (Figure 2).

Collaboration with competitors

The alternative would be working with competitors to overcome this insufficient data problem, perhaps using a centralised trusted body to pool data. This is not unfamiliar territory to insurers – think of sending mortality experience to the CMI to produce life tables, or using guidance from a reinsurance company that has the experience of many players in the market. Similarly, a collaboratively trained model could guide a company’s local model.

However, sending sensitive claims experience externally is not ideal. There may be no suitable centralised bodies that have the ability and capacity to perform calculations at speed before the experience is no longer relevant. Perhaps, due to funding arrangements, there are practical issues in setting such a body up. Or there may be issues around trust, data security and data privacy requirements.

Pooling model parameters instead of data

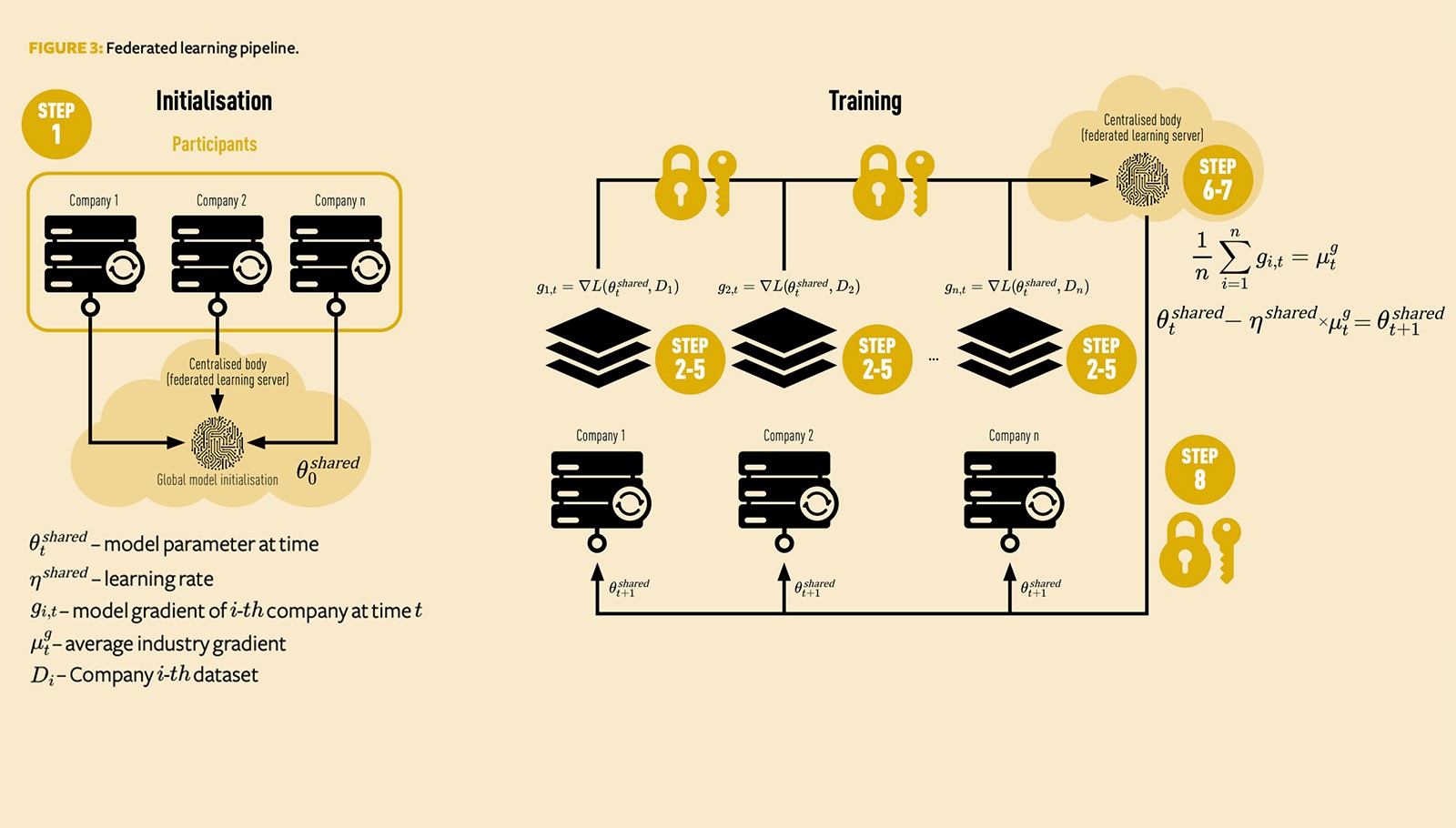

An alternative is to share model parameters, rather than data, using federated learning. The steps in the model training pipeline (Figure 3) are as follows:

- Initialisation step: All companies in the network agree on the same initial starting set of parameters, hyperparameters (such as learning rate

), loss function (L), and model architecture. Companies initialise the global model and define starting value of model parameters

.

- Every company¡ stores a local copy of this industry shared model. We denote any variables unique to them using subscript ¡ . Any variables shared by all the companies in the network are denoted by superscript shared.

- Each Company¡ tests this shared model against its historic experience by comparing the model’s predicted number of claims against the actual number of claims.

- Using the mutually agreed loss function L, Company¡ calculates model errors or residuals on its data – call it . The size and sign of these errors inform each Company¡ whether this shared initial model’s parameters are too big or small and need to be updated. Importantly, has not sent any data or output externally at this point.

- Rather than having each Company¡ use its error¡ to directly update its parameters, it is typical in machine learning to use the gradient with respect to some error cost function (such as sum of squares, Poisson deviance, and so on). The gradient measures how the output of this function changes with respect to changes in input. Gradient descent is implemented via:

Note that, at this point, every company has the same estimate of the global model at time, and they also have the same learning rate

. These are shared variables that were mutually agreed. The only difference is that each company has different errors or residuals due to the different data or experiences on their books, which means different gradients

. Without using the federated learning protocol, Company¡ would then update its parameters as follows:

Whererepresents a local gradient of Company¡ with a loss function run on D¡, which is Company¡ -th data. We have added shared and local superscripts to learning rate and model parameters to specify when variables are company-specific. However, since each company’s data is different, this update would lead to biased estimated model parameter updates. Some companies will have gradients that are too small, and some will have gradients that are too big.

- Instead, each Company¡ sends its

(not its data) to the central body, which calculates the industry average gradient. Assuming that there are

companies, this would be:

andrepresents the average of local gradients.

- The central body then, on its own server, calculates:

- This is then broadcast and sent out so that each Company¡ at time t + 1 receives

. Each

now receives new parameters that are calculated for them using a richer dataset. Therefore, their models generalise better against unseen data based on global parameters, compared to using

in step 5.

We then perform the following training steps:

Steps 2 to 8 are then repeated several times, with each keeping its data stored locally, the central body receiving updated gradients and companies in the network receiving their updates after each loop.

Adding security

While the centralised body only receives the model gradients, rather than the underlying data, this is still sensitive information that could be valuable to competitors. Companies could theoretically infer their competitors’ model errors and compare them with the size of their own errors (which ultimately relate to model parameters), using this information to gain a competitive advantage through knowing whether they have fewer or more claims than peers. Imagine if, when using simpler methods such as GLMs, everyone used the same distribution, link function and so on – the model coefficients would directly relate to the underlying data being fitted.

We therefore still need controls to make sure the centralised body is unable to identify individual participants, and that each participant’s model errors are secure. Even in the absence of collusion, we would still run the risk of a security breach via hacking or leaking.

These controls can be easily achieved, since the centralised body does not need to know which companies have which gradient; its main task is to compute the average of all the gradients, and it can do this without knowing the link between the company names and the data subsets. To implement this, an extension to PyTorch is needed, PySyft; this adds the required functionality for secure federated learning. PySyft uses modulo arithmetic, prime numbers, random noise and secure multiparty computation to mask where gradients are being sent from. When you send your gradient to the body, they cannot tell if it’s yours or your competitor’s – like using a VPN to mask an IP address, but without the need for a VPN provider.

Adding this final layer of encryption makes the entire process truly secure and encapsulates the main idea of federated learning – the model is taken to the data, not the other way around. Not even the raw model gradients leave the company. The effect is that companies train one global model through collaboration. Once the model is initialised and the model architecture defined, the participating companies train the global model locally and send back the gradients. The centralised body broadcasts model updates and the training process is repeated.

The results

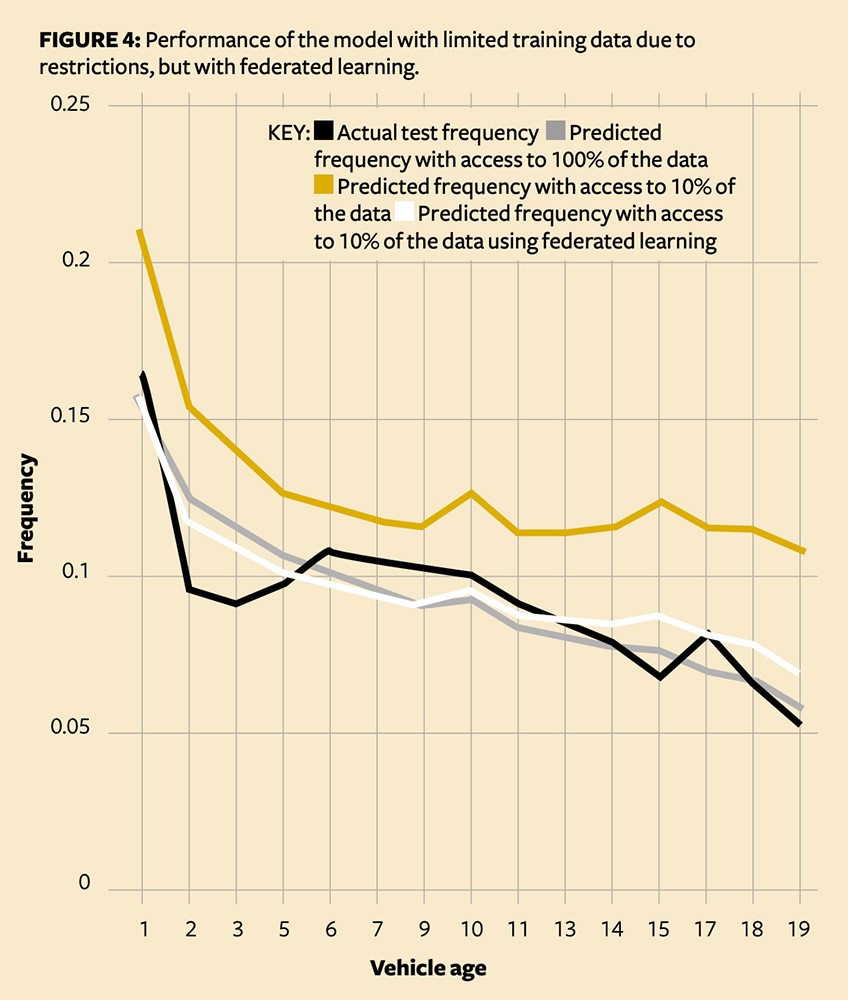

This ‘secret sharing’ step adds significant computation time to model building, and does introduce some noise. However, we can see that it significantly beats our initial partially trained model, and comes close to the ideal (Figure 4).

Federated learning in insurance

Federated learning allows insurance companies to exploit large amounts of multi-line data. While we considered 10 competitors joining forces here, the same principles could be applied to a large multinational that wanted to combine and utilise internal data – for example, mixing data from different business lines such as health and life, or building a shared model using experience from local sites. Regulators might benefit from federated learning in building more accurate diagnostic models, for example where sensitive medical health records are involved.

Federated learning could also help unlock the promise of wearables, the Internet of Things, autonomous vehicles and even telematics. Although revolutionary, these innovations still rely on a slow and expensive data gathering stage before being sent to the insurer, where it is cleaned further. Federated learning removes this by keeping all the data stored locally and deploying the model to the user. This could allow for incredibly rapid and dynamic consumer pricing, where not only are prices better aligned to risk, but they are also aligned fast.

Federated learning is likely to become the key technology that allows the training of AI models on multiple (distributed) data sources. Insurance companies might see the application of federated learning technology both in collaboration with third parties and in internal data management (to control data access within the organisation).

With federated learning it’s possible to build better predictive models that respect privacy, and introduce a new paradigm in which the model is brought to the data, rather than the data to the model.

Małgorzata Śmietanka is a PhD researcher in computer science at UCL

Dylan Liew is a qualified pricing actuary at Bupa Global

Claudio Giancaterino is an actuary and a data science enthusiast